Unicuspid Aortic Valves: What Should Patients Know?

Written By: Adam Pick, Patient Advocate, Author & Website Founder

Medical Expert: Samuel Pollock, MD, Cardiac Surgeon, Baptist Health Louisville

Published: September 20, 2022

According to the American Heart Association, unicuspid aortic valves are a rare disease in the general population. However, in our community, I have spoke with many patients who needed surgery due to these defective, one-leaflet valves that may cause stenosis and/or regurgitation. Normal aortic valves have three leaflets.

I recently received several important questions from Leslie, who asked me, “Hi Adam – What can you tell me about unicuspid aortic valves? How are they treated? Are they genetic? If so, should I have my family screened?”

To provide Leslie an expert opinion, I was fortunate to interview Dr. Samuel Pollock, a leading cardiac surgeon at Baptist Health Louisville in Kentucky. During his 25-year career, Dr. Pollock has performed over 12,000 cardiac procedures with more than 4,000 operations involving heart valve repair or replacement procedures.

Key Learnings About Unicuspid Aortic Valves

Here are the important points I learned during my interview with Dr. Pollock:

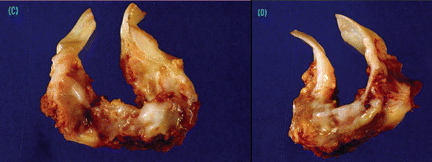

- Unicuspid aortic valves are not common. A unicuspid aortic valve has only one leaflet and often looks like a “volcano”, according to Dr. Pollock. Patients with malformed aortic valves more commonly have bicuspid aortic valves which have two leaflets. A normal aortic valve has three leaflets to manage blood flow through the heart.

Dr. Samuel Pollock (Heart Surgeon)

Dr. Samuel Pollock (Heart Surgeon)

- The detection of unicuspid aortic valves often occurs in newborns which may lead to treatment shortly after birth. “Most babies with unicuspid aortic valves are very ill,” states Dr. Pollock. “They’re treated in the first few days of life with a balloon valvotomy which is performed by a pediatric cardiologist. They put a balloon through the aortic valve and expand it. Sometimes, patients need an open valvotomy, which is a procedure done with a heart-lung machine where the valve is opened with a knife.”

- Children who undergo aortic valve treatment early in life often require an aortic valve replacement as they age. However, physicians often wait to perform an aortic valve replacement until the patient reaches an age between 18 and 21 years. “We don’t like to replace valves in younger children because they [the valves] don’t grow with the child,” states Dr. Pollock. “We like to wait until they’re 18 to 21 years old when the valve structure is almost adult size.”

- Treatment options for young adults include a tissue valve, a mechanical valve or a Ross Procedure. According to Dr. Pollock, the Ross Procedure is the best option for young adults.

Unicuspid Aortic Valve (Source: Andy Dial)

Unicuspid Aortic Valve (Source: Andy Dial)

- Unicuspid aortic valves are genetic. For that reason, Dr. Pollock recommends valvular screening for all family members. Screening tests including the use of a stethoscope and echocardiogram to detect turbulence across the aortic valve. Another screening tool includes genetic testing for aortic disease in patients with unicuspid and bicuspid valves.

Many Thanks to Dr. Pollock and Baptist Health Louisville

On behalf of the patients at HeartValveSurgery.com, many thanks to Dr. Samuel Pollock for sharing his clinical experiences and research with our community. We would also like to thank Baptist Health Louisville for taking such great care of heart valve patients.

Related Links:

Keep on tickin!

Adam

P.S. For the deaf and hard of hearing members of our community, I have provided a written transcript of my interview with Dr. Pollock below.

Video Transcript:

Adam: Hi, everybody, it’s Adam with heartvalvesurgery.com, and today we’re answering your questions all about unicuspid aortic valves. I am thrilled to be joined by Dr. Samuel Pollock, who’s a leading cardiac surgeon at Baptist Health, Louisville, in Louisville, Kentucky. During his extraordinary career, Dr. Pollock has performed over 12,000 cardiac procedures with more than 4,000 involving some form of heart valve repair or heart valve replacement.

Adam: It is great to see you and thanks so much for being with us today.

Dr. Pollock: Well, thank you, Adam. I’m glad to be here.

Adam: We’re going to get to Leslie’s question but first, Dr. Pollock, you’ve been a cardiac surgeon for over 30 years. I’ve got to ask you, why did heart valve repair and heart valve replacement procedures become such a very important part of your practice?

Dr. Pollock: Early in training at – when I was a resident, I became interested as we were doing all phases of cardiac surgery: valve repair, valve replacement at the University of Alabama in Birmingham with Dr. Kirkland at Pacifico. It was a large part of their practice, and I became interested, and I could see that it was really a big part of what they did day in and day out. You have to be a little bit of an artist to be able to do valve repair surgery and replacement surgery.

Adam: Dr. Pollock, I love you being an artist because you’ve been helping so many patients with your artistry there at Baptist Health Louisville. Now let’s get to Leslie’s question, and she asked, “Hi, Adam. What can you tell me about unicuspid aortic valves? How are they treated? Are they genetic? Should I have my family screened?”

Dr. Pollock: Yeah, they’re very rare. Most aortic valves have three parts. They’re called trileaflet valves. The most common abnormality in aortic valves and congenital, as you bring that up, is bicuspid valve that has two parts. Very rare is a unicuspid valve which has one part. They’re very strange-looking. They look like volcanoes. For the most part, they are genetic, and they do run in families, so we do recommend anybody that has a bicuspid valve or a unicuspid valve to be screened for genetics.

Adam: Dr. Pollock, for the treatment of unicuspid aortic valves, how are you doing that?

Dr. Pollock: Most of these babies with unicuspid valves are very ill, and they’re treated in the first few days of life with a balloon valvotomy, which the pediatric cardiologist does. They put a balloon through the aortic valve and expand it. Sometimes, they will need an open valvotomy, which is a procedure done with the heart-lung machine where the valve is opened with a knife. Now the valve is so abnormal that it will eventually have to be replaced. We don’t like to replace valves in younger children because they don’t grow with the child. We like to wait until they’re 18, 21 years old or the aortic and the valve structure is almost adult size; it can be replaced.

These days, there are several choices: a tissue valve, a mechanical valve, or a transfer, a Ross procedure where the pulmonary valve is transferred to the aortic position. In younger patients, this is the best option.

Adam: Dr. Pollock, you brought up a real interesting point about screening for unicuspid valves. I’m curious to know, how and who should be screened?

Dr. Pollock: The primary reason to check is to make sure that there’s not valvular heart disease in the rest of the family members. The best screening tool is a stethoscope, and usually a family doctor or a pediatrician can listen to the family’s heart and if they hear a heart murmur, which is turbulence across the valve, then it can be recommended to go to a cardiologist that does an echocardiogram to look at those.

The other thing that we look at is genetic testing for the associated aortic disease that we see with bicuspid and unicuspid valves. You can get blood tests to see if it runs in the family and if there are genetic markers that we would test family members for.

Adam: Dr. Pollock, that is very helpful, very important that patients and their family members should get screened for aortic valve disease. I didn’t know that about the markers and genetic testing, so thanks for sharing that. Leslie, I hoped this helped you learn a whole lot about unicuspid aortic valves. Dr. Pollock, on behalf of our entire community, I can’t thank you enough for taking time away from your very busy practice there at Baptist Health in Louisville and sharing this great research and insights with our community. Thanks for being here.