SAVR vs. TAVR Survival: Patients Over 65 Years Old

Written By: Allison DeMajistre, BSN, RN, CCRN

Medical Expert: Marc Gerdisch, MD, Chief of Cardiac Surgery, Franciscan Health

Reviewed By: Adam Pick, Patient Advocate, Author & Website Founder

Published: July 22, 2025

The field of heart valve replacement is an incredibly fast-moving space. It’s only been a little over a decade since the FDA approved transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for high-risk surgical patients. Now, with its approval for intermediate and low-risk patients, there are over one million TAVR patients worldwide.

However, many surgeons continue to recommend surgical valve replacement (SAVR) for intermediate and low-risk patients despite TAVR’s attractive benefits including no incision to the patient’s chest, shorter hospital stays and faster recovery. Surgeons are continually studying data comparing TAVR and SAVR to determine how each can address two of their most significant concerns: patient safety and long-term outcomes.

We received a patient question focusing on this important topic from Mossimo, who asked, “I found an interesting European study about outcomes of TAVR versus SAVR conducted on a group of over 19,000 people aged 65 or older. What this study is revealing is that in patients 65 years and older with severe aortic stenosis, selection for SAVR is associated with improved long-term survival compared with TAVR. Thoughts?”

We were able to get an answer for Mossimo from Dr. Marc Gerdisch during the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Conference in Los Angeles, California. Dr. Gerdisch is the Chief of Cardiac Surgery at Franciscan Health in Indianapolis. During his incredible career, he has performed over 4,000 heart valve procedures, and we were thrilled to hear his thoughts about TAVR versus SAVR research.

SAVR Versus TAVR in Patients Over 65 Years Old

Here are the key highlights shared by Dr. Gerdisch:

- Understanding TAVR and its consequences over time. “This is really fascinating,” said Dr. Gerdisch. “What we’ve been seeing is kind of a pendulum swing. I’m going to take the clock back about two years when we started seeing signals that transcatheter valves wouldn’t work out well for younger folks. There was this kind of fever that went across the entire nation with people under 65 receiving transcatheter valves. It came at such a pace that we started to recognize that we were suffering some ill consequences from that over time.” Dr. Gerdisch explained that they now understand the need to strategize for lifetime management while understanding more about the durability of transcatheter valves. “We have some ideas, but we don’t fully understand it. We know in younger people that tissue valves wear out faster and don’t last as long.”

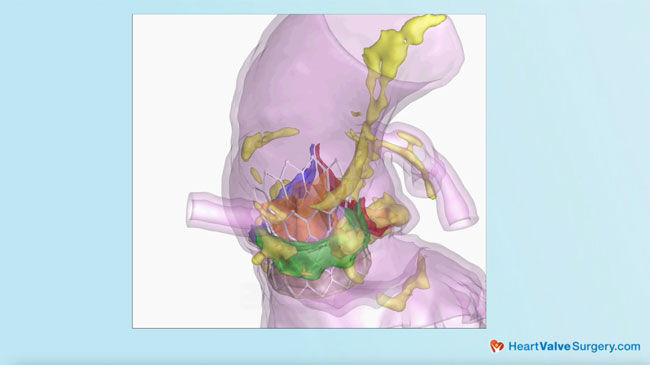

- Why do some patients over 65 do better with SAVR? “Transcatheter valves have been revolutionary,” said Dr. Gerdisch. “They have changed the trajectory of life for so many people and are a marvelous technology.” However, he explained that some patients over 65, particularly in some healthier subgroups with a physiology that gives them the opportunity to live a long time, may do better with a surgical valve. “When we put a transcatheter valve in, we challenge the native leaflets. Especially with aortic stenosis, where there is calcification in the leaflets. The bulkier the calcification, the worse the stenosis over time. This also means that bulky calcification out into the sinuses causes little bulges at the first part of the aorta. So, now you have this cylinder of a transcatheter valve with lumps of calcium surrounding it, which create “neo-sinuses,” or new sinuses created from the calcium masses inside those sinuses.

- Transcatheter valves continue to change in shape and size. “People thought that if you just move those calcium masses over, they will simply sit there, but it doesn’t do that. Instead, as people age with their transcatheter valves, the calcium masses change in shape and size, changing the flow dynamic of the aortic root and reorganizing the way the blood flow moves in the aortic root. So, what we thought might be a static situation is not. Anyone who has some longevity will see a continued change in the behavior of the tissue around the valve. That’s one of the things we see in the studies looking at explanted transcatheter valves in someone who died. We get to look at those valves, and the most recent paper out of Vancouver that looked at the calcification around the valve showed us that it changed.”

- Valve deployment is not perfect and contributes to potential complications. Dr. Gerdisch said, “The other thing that is revealed every time we look at large numbers of transcatheter valves is that they are not perfectly deployed. If they got perfectly deployed, you’d have a perfect circle; all leaflets work how you want them to. But most of the time, that’s not what the root architecture allows. So, you have one leaflet that doesn’t move quite as well, with the potential of forming a thrombus and diminishing the valve’s longevity. In my mind, this shows the difference between the surgical valve, where we cut everything out and sew the valve so that it stays that way until it deteriorates inside a tissue valve. In a transcatheter valve, we implant it, and we may think it looks good, but we don’t have the granular information.”

- Common findings when comparing transcatheter versus surgical valves immediately after treatment. Dr. Gerdisch explained that without getting into the absolute numbers that confounding factors can’t account for, studies do show a common factor when comparing transcatheter to surgical valves. “Every time we look, we see two things. Immediately at the time of the procedure, the advantage goes to transcatheter valves with respect to complications, which makes sense. You come in, do your valve, and go home the same day. The only complication that we see more in transcatheter than surgical valves is pacemakers. In places that do a lot of SAVRs, the is probably two and a half or three percent and nationally it might be four and a half percent, but with transcatheter valves that rate would never get that low. But the other complications are about equal including the incidence of stroke and mortality depending on the subpopulation of patients.”

- The comparisons change over time. “When you get out to about three years, we consistently see that the lines start to get close on mortality. Once you get out to five years, you start to see a distinct difference. There is some recent data published at ten years and it’s pretty stark with a big difference in survival.

- Patients over 65 could need their replacement valve for quite some time. “The average 63-year-old in the United States has a further lifespan of 20 years. Some 65-year-olds will live another 30 or 35 years. So, if we have a 65 or 70-year-old that is robust, there is a good chance we are going to be dealing with that valve for quite a long time.” Dr. Gerdisch explained that this further longevity is why the data shows that survivability with SAVR becomes better over time than with TAVR. “Tissue valves are not static. As soon as a tissue valve goes in, they are subject to your immune system and the milieu that they are in. They are all going to start to deteriorate and if those leaflets aren’t perfectly expanded, if there’s any pinwheeling of the valve like is seen with TAVR, then we will see some accelerated deterioration and I think we start paying that price. We get three, four, or five years out and that’s why we see this data showing up now. We needed the time after putting those valves into people legitimately and appropriately and then make those comparisons.”

Thanks Dr. Gerdisch and Franciscan Health!

On behalf of all the patients in our community, thank you Dr. Marc Gerdisch, for everything you and your team are doing at Franciscan Health!

Related Links:

- Stroke Risk & Heart Valve Calcification: What Should You Know?

- See the Top 5 Facts for Newly Diagnosed Patients

- Watch the Patient Webinar, “Ask Dr. Gerdisch Anything”

Keep on tickin,

Adam

P.S. For the deaf and hard-of-hearing members of our patient community, we have provided a written transcript of our interview with Dr. Gerdisch below.

Video Transcript:

Adam Pick: Hi everybody, it’s Adam with HeartValveSurgery.com and we’re in Los Angeles, California at the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Conference. I am thrilled to be joined by Dr. Mark Gerdisch who’s the Chief of Cardiac Surgery at Franciscan Health in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Dr. Gerdisch, you and I have known each other for over 10 years. It is great to see you again and thanks for being with us today here at STS. Thanks for being with me.

Dr. Marc Gerdisch: Thanks, Adam. Pleasure to be here.

Adam Pick: Dr. Gerdisch, there’s a lot of great presentations and research being shared here. You’re giving talks and we’re also getting questions from patients coming in from all over the world.

And this one comes in from Mossimo who asks, “Hi Adam. I found an interesting European study about outcomes of TAVR versus SAVR conducted on a group of over 19,000 people aged 65 or older. What this study is revealing is that in patients aged 65 years and older with severe aortic stenosis. Selection for SAVR is associated with improved long-term survival compared with TAVR. Thoughts?”

Dr. Marc Gerdisch: This is really fascinating. What we’ve been seeing is kind of a pendulum swing. I’m going to take the clock back maybe two years when we started to see signals in younger folks that transcatheter valves weren’t going to work out well for them. There was this kind of fever that went across the entire nation and people under 65 were receiving transcatheter valves.

It still happens some. It came at such a pace that we started to recognize that we were suffering some ill consequences from that over time. The reason for that is because we have to strategize on lifetime management. We also don’t really understand fully the durability of transcatheter valves.

We have some ideas, but we don’t fully understand it. And we know in younger people that tissue valves wear out faster. They don’t last as long. So, we have that, and then now, what’s being pointed out here is that even in folks that are over 65, we may see a signal, especially in some subgroups, especially the healthier ones, that those people who already have cooked into their physiology the opportunity to live a long time, they may do better with a surgical valve.

So, why does that even happen? So, there’s a few different things to think about. One of them is that when we put a transcatheter valve in, and this is just kind of some simple science and physics of the space and the aortic valve.

When we put a transcatheter valve in, and by the way, transcatheter valves have been revolutionary. They have changed the trajectory of life of so many people. They are really a marvelous technology.

But, when we put a transcatheter valve in, we force the native leaflets. So, especially aortic stenosis, right, so we’ve got aortic stenosis, which means we’ve got calcification in the leaflets. The bulkier the calcification, the worse the stenosis most of the time, but also that means we move that bulky calcification out into the sinuses, so the sinuses are the little bulges at the first part of the aorta.

So, now you’ve got this cylinder of a valve, whatever transcatheter valve it is, and then you have these, these kind of lumps of calcium around them. They create what are called neo-sinuses. This is the new sinus that’s there because we have this, these masses that are in those sinuses. So, here’s the punchline though.

People kind of thought, well, you just move it over and just sit there, but it doesn’t do that. It actually continues to change. So, as people age in with their transcatheter valves, those masses are actually changing in shape and size, and changing the flow dynamic in the aortic root, and reorganizing the way the blood flow moves in the aortic root.

So, what we thought might be a static situation isn’t. So, in that sense, kind of just from a, pathology within the aortic root sense, anybody who’s got some longevity, they’re going to see some continued change in the behavior of that tissue around the valve. Now you take that and you compound the impact of the unlikelihood that with every patient that you get a perfectly deployed valve because you don’t, okay?

That’s one of the things that we see in the studies looking at explanted transcatheter valves whether that be in someone who died, we get to look at those valves and in the most recent paper, it came out of Vancouver, and they were looking at the calcification around the valve and showing us that it actually changed.

But, the other thing that is revealed every time we look at large numbers of transcatheter valves is they, they’re not perfectly deployed. If they get perfectly deployed, you got a perfect circle and all leaflets are working the way you want them to. But, most of the time that’s not what the architecture of the root allows.

So, you’ve got one leaflet that doesn’t move quite as well. And if that’s the case, then you have the potential performing thrombus there and diminishing the longevity of the valve. So, in my mind, this kind of mostly goes to the difference between the surgical valve, we cut everything out, we sew the valve in just the way we put it in and it stays that way until the valve deteriorates in a tissue valve.

In a transcatheter valve, we implant it and we think it looks good, but we don’t have the granular information. So, if we look at all the studies that have tried to compare transcatheter to surgical valves. The really common finding, without getting into the, the absolute numbers, because the reason I don’t want to get into absolute numbers is because when we make these comparisons, there are confounding factors that we can’t account for, like just the impression of the patient when he operated on him or did the transcatheter valve, the sensibility for that patient.

But, every time we look, we see two things – that immediately at the time of the procedure advantage goes to transcatheter valves with respect to complications, right? Just kind of makes sense. You come in, do your valve, you go home the next day. The only complication that is always better in surgery, with surgery, is pacemakers.

So especially in places that do a lot of aortic valve replacements, pacemaker rate is probably two and a half, three percent. We look at it nationally, it might be four and a half percent or something like that. And transcatheter valves would never get that low. But, the other stuff is about equal, the incidence of stroke, mortality, and depending on the subpopulation of patients.

When you get out to about three years is when we consistently see that the lines start to get close on mortality, which is what we’re talking about. And you get out past three years, you get out to five years or so, you start to see a distinct difference. So, there’s some recent data published at ten years.

And it’s pretty stark. I mean, it’s a big difference in survival. So, in summary, someone over 65 might be 68 or they might be 70. And, in the average 63 year old in the United States has about a 20 year on average, a 20 year lifespan. Now, some 65 year olds hopefully are going to, you know, 63, 65 year olds are going to live 30 years or 35 years, but on average.

So, if we’ve got a 65 or 67 year old, someone over 65 or 70 year old that is robust, there’s a good chance we’re going to be dealing with that valve for quite a long time. And that’s how this happens, right? It’s, the valve is not static. Tissue valves are not static. As soon as they go in, any tissue valve, they are subject to your immune system and the milieu that they’re in.

So they’re all going to start to deteriorate and if those leaflets aren’t perfectly expanded if there’s any pinwheeling of it, etc. Then we’re going to see some accelerated deterioration and I think we start paying that price. We get three four or five years out and that’s why we see this data showing up now. Because we needed the time we needed to put those valves and people legitimately and appropriately and then make those comparisons.

Adam Pick: Mossimo. I hope that helped you. I know it helped me and Dr. Gerdisch on behalf of Mossimo and all the patients in our community. Thanks for everything you and your team are doing at Franciscan Health in Indianapolis, Indiana. Thanks for being with me today.

Dr. Marc Gerdisch: Thank you. It’s our pleasure.