Surgeon Q&A: Transcatheter Mitral Valve-in-Valve Procedures

Written By: Allison DeMajistre, BSN, RN, CCRN

Medical Expert: Marc Gillinov, MD, Chairman of Cardiac Surgery, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

Reviewed By: Adam Pick, Patient Advocate, Author & Website Founder

Published: December 4, 2025

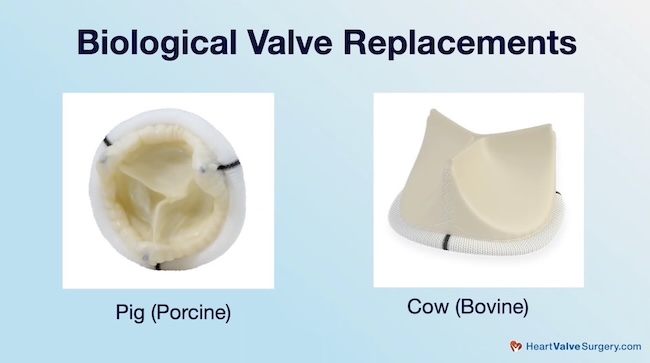

Patients who choose a tissue mitral valve replacement instead of a mechanical valve understand that at some point in the future, they may need to have the valve replaced again. Unlike mechanical valves, which are designed to last a lifetime, tissue valves typically deteriorate after about 10 to 15 years after implant. Many patients are willing to trade-off the durability of a tissue valve for the burden of lifelong anticoagulant medication required for mechanical valves. The good news for patients with a failing tissue mitral valve is that instead of heading straight for the operating room for another cardiac surgery, patients may be candidates for a less invasive transcatheter “Valve-in-Valve” procedure.

Adam Pick, the founder of HeartValveSurgery.com, recently met with Dr. Marc Gillinov to find out more about the latest updates on transcatheter mitral valve-in-valve techniques. Dr. Gillinov is the Chairman of Cardiac Surgery at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio, and an expert in mitral valve repair and replacement.

Transcatheter Mitral Valve-in-Valve Techniques

Here are the key insights shared by Dr. Gillinov during our video interview:

- The options for replacing a tissue valve. Dr. Gillinov explained that tissue valves, which are either made from pig or cow valves, typically last around 10 years. “I’ve seen seven years, I’ve seen 22 years,” he said. “But let’s say you got a pig valve, it’s 10 years later, and it’s worn out, so you need a new one. How are we going to get a new valve in there? There are two ways to go. One way is with traditional surgery, where we make an incision, which could be through the side or the front. We surgically remove the old valve and replace it with a new one, offering you a choice between a tissue valve and a mechanical one. The second way, which is newer, is that you replace it with a valve-in-valve.”

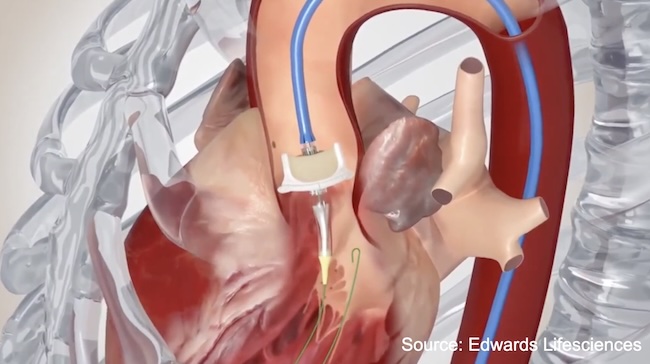

- The transcatheter valve-in-valve procedure. “We take a new valve, and we compress it or fold it like an umbrella so it’s very thin,” Dr. Gillinov explained. “We thread it up a vein in your leg into the heart and then deploy it in the housing of the old pig valve, just like opening the umbrella. The reason this works is that the pig valves and the cow valves are generally circular, so they’re a circle. It’s a perfect landing zone to open that new valve, like opening a round umbrella, and it stays where we put it.”

- Patients should collaborate with their cardiac team to decide the replacement procedure that’s best for them. “If you have a worn-out bioprosthetic valve, you should definitely ask your cardiologist and your surgeon about how the replacement should be done. Are you a candidate for the less invasive valve-in-valve procedure, or is there something about your anatomy and previous valve that makes surgery a better option? It’s not that one is better than the other; it’s really just what is best for you.”

- Since valve-in-valve techniques are relatively new, what data are available on the durability and performance of the valves and the procedures? “That is the really big question,” said Dr. Gillinov. “These valve-in-valve procedures, where we put a new valve inside the housing of an old valve, are pretty new, and we do not know how long those valves are going to last. At three, four years, they’re looking all right, but what does that mean?” Dr. Gillinov explained that if someone is 60 or 70 years old, they may opt for a new surgical valve that will probably last a lifetime. On the other hand, for someone who is 80 years old with a pig or cow valve that’s worn out, a valve-in-valve may be more appropriate.”

Thanks Dr. Gillinov and Cleveland Clinic!

On behalf of all the patients in our community, thank you, Dr. Marc Gillinov, for everything you and your team are doing at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio!

Related links:

- See 100+ Patient Reviews for Dr. Gillinov’s Interactive Surgeon Profile

- Surgeon Q&A: 3 Facts to Dispel Patient Anxiety Before Heart Surgery

Keep on tickin,

Adam

P.S. For the deaf and hard-of-hearing members of our patient community, we have provided a written transcript of our interview with Dr. Gillinov below.

Video Transcript:

Adam Pick: Hi everybody. It’s Adam with HeartValveSurgery.com, and we are at the Endoscopic Cardiac Surgeons Club meeting in northern Kentucky. I am thrilled to be joined by Dr. Mark Gillinov, who’s the chairman of Cardiac Surgery at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Gillinov, ou and I have known each other for a long time. It is great to see you again. Thanks for being with me.

Dr. Marc Gillinov: My pleasure.

Adam Pick: We’re here. We’re learning a lot, all about minimally invasive techniques. We’re also getting questions from patients coming at us. One of them is all about transcatheter mitral valve in valve procedures. Can you share with the patients what are the latest updates on this technique?

Dr. Marc Gillinov: Sure. The valve in valve procedure. What we’re talking about is somebody got a tissue valve, a bioprosthetic valve, usually a pig valve or a cow valve previously. And these valves, these cow pig valves will usually last around 10 years. I’ve seen seven years, I’ve seen 22 years. But let’s say you got a pig valve and it’s 10 years later and it’s wearing out, you need a new one.

How are we going to get a new valve in there? And there are two ways. One way is traditional surgery where we make our incision, and it could be through the site, the front. We take the old valve out surgically and put a new valve in. And your choice if you get a tissue valve or a mechanical valve. Second way that’s newer is what you set a valve in valve.

What that means is we take a new valve and we compress it or fold it like an umbrella, so it’s very thin. We thread it up a vein in your leg into the heart, and then deploy it in the housing of the old pig valve, like opening the umbrella. Why does that work? Because the pig valves and the cow valves are generally circular, so they’re a circle.

It’s a perfect landing zone to open that new valve, like opening a round umbrella and it stays where we put it. What does that mean? It means that if you’ve got a worn out bioprosthetic valve, a worn out pig valve, or a worn out cow valve. You should definitely ask your cardiologist and your surgeon, how should I get my new one? Am I a candidate for the less invasive valve and valve procedure, or is there something about my anatomy and my previous valve that means heart surgery’s going be a better option for me? It’s not a one’s better than the other. It’s really a what’s the best for you.

Adam Pick: Great, and I have to ask you a follow up question. Some of these valve and valve techniques are relatively new in the field of cardiac therapy. Do we have any data about the durability and the performance of these valve and valve procedures?

Dr. Marc Gillinov: That is the real big question. I mean, you just hit on it. These valve in valve procedures where we put a new valve inside the housing of an old valve are pretty new, and we do not know how long those valves are going to last.

At three, four years, they’re looking all right. Um, but what does that mean? It means to me if, if I’m 60 or 65, or perhaps 70, I probably opt for a new surgical valve that I know is probably going to last my whole life. On the other hand, if I’m 80 years old and I’ve got a pig or a cow valve that wore out, I’d probably be thinking, let me try the valve-in-valve.

Adam Pick: On behalf of the patients in our community, patients all over the world. Dr. Gillinov, thanks for this update on transcatheter valve and valve procedures for the mitral valve, and thanks to everything you and your team are doing at the Cleveland Clinic. Thanks for being with me today.

Dr. Marc Gillinov: My pleasure.