Pediatric Heart Valve Surgery: What Should Parents Know?

Written By: Adam Pick, Patient Advocate & Author

Medical Expert: Richard Kim, MD, Surgical Director, Guerin Family Congenital Heart Program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Published: October 21, 2021

Congenital heart defects are the most common type of birth defect.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, congenital heart defects are present at birth and can affect how blood flows through the heart and body. There are several different types of congenital heart disease which may impact the functioning of one or more of the four valves within the heart. For example, Tetralogy of Fallot is a congenital heart defect which compromises the ability of the pulmonary and aortic valve to effectively move blood through the heart.

To learn about the diagnosis, the management and the treatment of pediatric heart valve disease, we interviewed Dr. Richard Kim, Surgical Director of the Guerin Family Congenital Heart Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. During his extraordinary career, Dr. Kim has performed over 2,000 cardiac procedures.

Key Learnings About Pediatric Heart Valve Surgery

Here are several important points that Dr. Kim shared during our interview:

- Dr. Kim’s passion for cardiac surgery began in medical school after he saw his first heart operation. Dr. Kim became fascinated by the significant and positive impact a successful cardiac surgery could have on patient life. Specific to pediatric heart surgery, Dr. Kim’s passion for treating children expanded when Dr. Kim became a parent himself.

Dr. Richard Kim

Dr. Richard Kim

- Congenital heart disease is a defect that a child is born with. The defect occurs as the child develops during pregnancy. A bicuspid aortic valve is common form of congenital heart disease in which two of the three leaflets within the aortic valve fuse together during pregnancy.

- There are many opportunities to detect congenital heart disease throughout the different stages of a patient’s life. At 18-20 weeks of pregnancy, a fetal ultrasound can identify congenital heart disease in utero. At birth, an oxygen test can detect congenital heart disease. A stethoscope will often identify congenital heart disease in young children and adults when a murmur is heard by a physician.

- Common symptoms that may be experienced by patients with congenital heart disease include shortness of breath and fatigue.

- Dr. Kim suggests that parents often feel an extreme amount of guilt that they were responsible for passing congenital heart disease to their children. While there are types of congenital heart disease that include a genetic component, the vast majority of congenital heart disease is not inherited from the parents.

- The treatments for congenital heart disease can range from a simple intervention to challenging and very complex procedures that transform the physiology of the heart.

- According to Dr. Kim, the most common misconception about pediatric heart valve surgery is that a single procedure will “fix” the heart. Instead, Dr. Kim suggests that families regularly follow the patient’s congenital heart disease which may require multiple interventions during the patient’s life.

- The field of pediatric heart valve surgery is rapidly advancing. New therapies may use minimally-invasive devices and leverage a hybrid approach of surgical and interventional techniques. One example of this innovation is a new dilatable heart valve that can grow (be expanded) as the child grows.

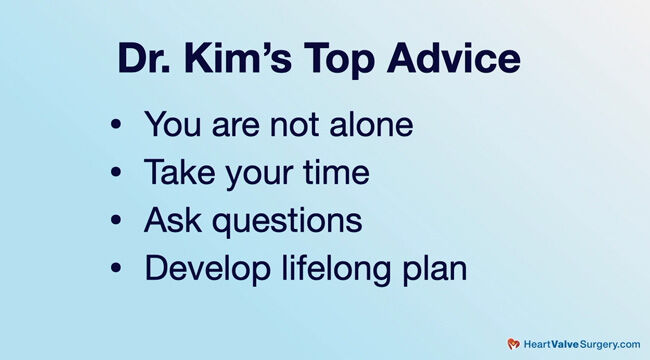

- Dr. Kim’s advice for parents is (i) to realize that you are not alone, (ii) to take your time when identifying your medical team / treatment plan, and (iii) to remember that congenital heart disease is a life-long disease that needs to be followed by an experienced and specialized medical team.

Many Thanks to Dr. Kim & Cedars-Sinai!!!

On behalf of our entire patient community, many thanks to Dr. Kim for sharing his clinical experience and research with our community! Also, many thanks to the Cedars-Sinai team for taking such great care of heart valve patients!

Keep on tickin!

Adam

P.S. For the hearing impaired members of our community, I have provided a written transcript of my video interview with Dr. Kim below.

Video Transcript:

Adam Pick: Hi, everybody. It’s Adam with heartvalvesurgery.com, and this is a very important surgeon question and answer session all about pediatric heart valve surgery. I’m thrilled to be joined by Dr. Richard Kim who’s the surgical director of the Guerin Family congenital Heart Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. During his extraordinary career, Dr. Kim has performed over 2,000 procedures of which many have involved some form of valve repair or valve replacement. Dr. Kim, I’m really excited for this conversation. Thanks so much for being with us today.

Dr. Kim: Thanks for having me. It’s nice to see you.

Adam Pick: Dr. Kim, before we get into the Q&A all about pediatric heart valve surgery, I’ve got a question all about you. When and why did you know that you wanted to be a pediatric heart surgeon?

Dr. Kim: I always love the heart and lungs and the physiology when I was in medical school, but really, when I first saw a heart operation, I knew that there was nothing else that – where you could really impact and change a patient’s life so dramatically. It was something I knew I really wanted to be a part of, and then pediatrics was just an extension of that. There really was nothing that I saw where you could have such a tremendous relationship with your patients and the parents of the children that you were helping. It became very, very important to me also when I became a parent myself, and it made me really appreciate and really love the field in a completely different way.

Adam Pick: That’s a great story Dr. Kim about you becoming a parent and really amplifying your passion for this profession. I’m so thrilled it’s worked out for you. Now maybe we can take a step back and ask and answer a question that I’m sure is on a lot of people’s minds who are watching this. That is what is congenital heart disease.

Dr. Kim: That’s a question that comes up a lot, actually, and the difference between congenital and acquired heart disease, which is the adult form of disease and the one you typically think of, like for instance, a leaking valve or a heart attack, needing to have a heart bypass operation, congenital disease is disease that a child is born with. It’s a problem of the development of the heart and the valves themselves.

Adam Pick: Dr. Kim, very helpful in helping us understand about congenital heart disease. Let’s talk about some of the valvular disorders and most importantly the detection of typical types of diseases like stenosis and regurgitation. How does that occur for congenital patients?

Dr. Kim: Congenital heart disease can be detected at many, many different stages in a patient’s life. Many times, it can be detected in utero with a fetal ultrasound. Usually, every child gets an ultrasound around 18 to 20 weeks prenatally. Sometimes it can be detected as soon as a child is born. All children need a oxygen test, and sometimes when the oxygen is low it clues us into maybe there’s a problem with the heart. Then sometimes children in the school age develop a murmur, and that can be picked up by their pediatrician. Incidentally, congenital heart disease can present as an adult, and sometimes, adults can suffer some of the same problems that the children do and may come in because they’re short of breath or they’re having difficulty doing some of their activities. Throughout a patient’s life you can really detect – there are different stages to detect congenital heart disease.

Adam Pick: Dr. Kim, it’s great to hear about all the ways that you and the Cedars team can detect congenital heart valve disease, and I can remember has a congenital heart valve patient, I had questions like did I do something wrong to cause this, or is this genetic. I imagine that there are other patients out there and parents as well who have those questions. Can you talk about that?

Dr. Kim: Adam, I’m so glad you asked this question actually because it’s a question that we see a lot. I would say that overwhelmingly, we actually don’t know why children get congenital heart disease. I get the question from parents a lot did they inherit the disease from me. Is there something that I passed on, and parents feel a tremendous amount of guilt. Although we do know that for some cases of congenital heart disease there’s a genetic component, overwhelmingly usually it is not inherited.

Adam Pick: Dr. Kim, what are the different types of therapies that you and your team might use there to help congenital heart disease patients with valvular disorders?

Dr. Kim: The number of problems that congenital heart surgeons deal with can be vast, and the therapies that we use to address each one of them can range wildly from very small interventions to very complex ones where we’re moving the great vessels or we’re transforming the physiology of the heart. Different things like different surgical procedures, combinations of surgical and interventional procedures, really the key is that we as other places have a tremendous team, and working together, we can really offer therapies for just about every congenital heart problem.

Adam Pick: Dr. Kim, can you share for the parents and the patients out there what might be some misconceptions about pediatric valve surgery?

Dr. Kim: I think the biggest one is that once you have an operation that’s it, that the heart is going to be fine and that the problem is really taken care of. It is really important particularly in congenital disease that the family follow up with their cardiologist and their cardiac surgeon for life. It really in most cases is something that really needs to be treated over a lifetime.

Adam Pick: Dr. Kim, medicine is these days having a series of advances in technologies, procedures, and techniques. Do those evolutions and innovations also apply to pediatric valve therapy?

Dr. Kim: Like everything, the field is growing, and the future is very bright. I think some of the things that we’ve done is we’re able to use devices that are much smaller, for instance, or we’re able to use devices in combination with interventional approaches and surgical approaches. One example is using a dilatable valve or a valve that you can make bigger and use it in the mitral valve location. Obviously, one of the biggest problems with operation on children is that children grow and valves generally do not, but using – applying some of these interventional techniques like putting a dilatable valve in the mitral valve position and then allowing it to dilate over time, we’re able to help mitigate some of the potential problems that children face as they grow.

Adam Pick: Dr. Kim, for the parents out there who are watching this and might actually be struggling a bit with this news that their kids have some form of congenital heart valve disease, do you have any advice for them?

Dr. Kim: This is really important, I think. The first thing is that you’re not alone. Number two is take your time, and don’t be afraid to ask any questions of the team. Really, it’s okay to be thoughtful and to be even a little selfish in terms of deciding the treatment plan. It is your child. Then finally that congenital heart disease is a lifelong disease. It’s a disease that really needs to be followed by an experienced team over the lifetime of your child.

Adam Pick: Dr. Kim, on behalf of the entire community of heartvalvesurgery.com, thanks so much for taking time away from your very busy practice there at Cedars-Sinai to share this very important information about congenital heart disease with our community. Thanks so much.

Dr. Kim: Thank you, Adam. I really enjoyed it.